Preface

I wrote this review for the Non-Book Review Contest on Scott Alexander’s blog. That blog has some of the finest writing on the Internet. Every year, it organizes a contest where readers can submit articles. After a voting phase, the ten best articles are published on the blog, and readers chose a final winner among those.

My entry was far from entering the finals. It was ranked in the first half of the submissions though. This convinced me that it’s not crap ;-) and motivated me to publish it here.

You might like this post if you don’t know much about the Toki Pona language, and are curious to learn more. I tried to make it humorous, and added many references to Scott Alexander’s blog or his book Unsong.

The Language of Good

Scott Alexander: Alice, hello!

Alice: toki! I am jan Alise. I have found simplicity. I have found goodness. I speak Toki Pona now.

Scott: Excuse me, I meant to ask you to participate in a dialogue on my blog. You and Bob are to discuss the inherent complexity of drug reviews. You conclude that there are no simple good solutions, only trade-offs.

jan Alise: There is always simplicity and goodness. That is the essence of Toki Pona.

Scott: Alright, what is Toki Pona?

jan Alise: Toki Pona is the language of good. It has 120 words.

Scott: I’m good with languages, Alice, but even I can’t describe drug reviews using 120 words.

jan Alise: The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 170,000 words. Your typical blog post uses about 1200 of them 1. That’s less than 1%! Surely, this is nowhere near the lower limit. Surely, it is your skill in arranging the words that makes your texts great, not the size of your vocabulary.

Scott: Well… how would you explain drug reviews to me in 120 words?

jan Alise: Step by step. Idea by idea. The first step is to understand. We have a saying: “sina ken ala toki pona e ijo la, sina sona ala e ijo” – if you can not say simply a thing, you understand not the thing.

sina ken ala toki pona e ijo la, sina sona ala e ijo – by jan lili Enta, a member of the Toki Pona community. The text is written in the “Sitelen Suwi” decorative writing system, using a custom glyph for the second “ijo”.

Scott: This sounds like Yoda.

jan Alise: Well, we put adjectives behind nouns. The grammar is different from English, but simple and regular. Would you like an introduction?

lazy Scott: Nah, thanks! I’ll turn this into an interactive blog post and skip forward seven paragraphs.

curious Scott: Yes, please! I’m always eager to learn more about languages. How does that sentence work?

Toki Pona Grammar in a Nutshell

jan Alise: Sentences have the form <subject> li <verb> e <object>. For example, “sina toki e ijo” means you describe a thing. The particle li is omitted if the subject is mi or sina – I or you.

Modifiers go behind the thing that they modify. Examples are “sina pona li toki e ijo” – the friendly you describes a thing (note the li, since the subject is no longer simply “sina”). “sina toki pona e ijo” – you describe a thing well. “sina toki e ijo pona” – you describe a good thing.

Almost all words in the language can take any function. “pona” as a noun means goodness or simplicity. As an adjective, it can mean good, positive, simple, friendly… and as an adverb, it means well or simply. As a verb, it means to improve or to simplify. This is why the particles li and e are important – they make it clear where the subject end and the verb starts, and whether there is an object.

Pre-verbs add nuance to a verb. In the proverb, there is the preverb “ken”, meaning to be able to. It is modified using “ala”, which means not: “sina ken ala toki pona e ijo” – you cannot explain a thing simply.

The proverb features one more particle, “la”. It is a context marker. Everything before the “la” is context for what comes afterwards. In this case, the result is an if-then sentence: “sina ken ala toki pona e ijo la” – if you cannot explain a thing simply, then… “sina sona ala e ijo” – you do not know the thing.

“la” is the only form of sentence-level recursion in Toki Pona. Like the Pirahã Language, Toki Pona has very short sentences. More complex thoughts have to be split. For example: Alice says that you know the thing becomes two sentences: “jan Alise li toki e ni: sina sona e ijo” – Alice says this: you know the thing.

jan Alise: That’s all the grammar you need to understand all I’ll be saying in Toki Pona. I’ll still give you English translations, but I’ll use more natural English now, no more Yoda-style sentences with Toki Pona word order!

* * *

Scott: So in this sentence, “toki pona” means to explain in simple terms?

jan Alise: It means that. And also “the good language”. And also “the simple language”. And also “clear communication”. And…

Scott: Wait! You preach simplicity, but deliver ambiguity. How would anyone understand what you are saying?

jan Alise: Each word in Toki Pona represents a concept. Its semantic space can be quite large, but it encapsulates one idea. “pona” means good, simple, pleasant, beautiful… if something evokes positive feelings, it is pona.

Scott: A hedonistic language, eh? I still don’t see how imprecision is useful.

jan Alise: Think of it as an art. For example, when someone says “make America great again”, the word “great” is deliberately ambiguous. It means a different thing to each person. English obscures this ambiguity, but Toki Pona makes it plain and clear.

Scott: What if I want precision?

jan Alise: You can be as precise as the context requires. “sina pona” means you are good. And beautiful. And kind. You can add more modifiers to narrow down the meaning. “sina pona insa” means you are good in an inside way. As in, you have a good heart. “sina pona tan ni: sina pana e pona tawa jan mute pi mani ala” means you are good because you give help to many people with no money. You are an altruist.

Scott: It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a language in possession of few words, must be in want of extremely long explanations. Why prefer a page of explanations when the two words effective altruist suffice in English?

jan Alise: Have you not written thousands of words to explain what effective altruist truly means?

Scott: Touché. But I am not letting you off the hook so easily. Surely having only 120 words makes explanations less precise?

jan Alise: Consider P(A|B) = [P(A)*P(B|A)]/P(B) – ultimate precision with minimal words.

Scott: You are cheating. This only works because people have a shared understanding of P, A, and B.

jan Alise: Okay. If language is the shared foundation on which we construct explanations, then what makes a good language? Maybe a perfect shared understanding of 120 words is better than fragmented knowledge about some subset of 170,000 words?

Scott: Do people have such a perfect understanding? Who defines what a word means?

jan Alise: That’s a good question. I believe words are well-defined in practice because they represent universal concepts. Take something like “luka”, which is usually translated as hand or arm. Everyone knows what that is. At the same time, we can combine “luka” with other words in a way that feels quite natural: A fish hand is probably a fin. A tree hand is probably a branch. “luka” as a verb usually means to touch or hold, because that’s what hands do. Because there are so few words in the language, “luka” can fill the entire space of hand-related concepts without conflicting with another word.

As for who defines the meaning… Sonja introduced most words when she created the language back in 2001. Since then, a few words have seen changes in their use, and a handful of new words have become accepted in the community. By and large, the language is stable because it focuses on these universal human experiences.

Scott: So again… how would you explain the FDA’s drug approval process with 120 words? The challenges faced by the FDA aren’t exactly universal human experiences.

jan Alise: Let me try to break down the core idea: “wile tu li lon” – two needs exist. “wile nanpa wan li ni: pona o kama” – need #1 is this: goodness shall happen. “wile nanpa tu li ni: ike o kama ala a” – need #2 is this: badness shall absolutely not happen!

Scott: Alice, I want to write about drug reviews. You have a point, but it’s absurdly generic. This applies just as well to AI accelerationism vs AI safety. Or to the YIMBY/NIMBY debate.

jan Alise: NEW BLOG POST: Toki Pona speaker discovers hidden connection behind world’s most pressing problems!

Scott: This all sounds too simplistic to me. And boring. Who would read a blog post about the FDA if there aren’t any puns?

jan Alise: We have them too. Consider this one: The table broke. How terrible!

Scott: …

jan Alise: supa li pakala. IKE A!

Scott: Alice, you are cherry-picking! With 120 words, there are 14400 two-word combinations. Let’s say one in a thousand are funny, that leaves you with just a dozen puns, barely enough for a single blog post. I’m telling you, this language is too limiting.

jan Alise: Consider the bright side. You have seen 31/120 words by now. That’s about a quarter of the vocabulary. In relative terms, you know Toki Pona better than an educated English speaker knows English. 2

Scott: I hope you aren’t going to shoehorn all 120 words into this everything-except-drug review! That would be depressing.

jan Alise: Haha no! But speaking of depression, did you know that Toki Pona started when someone named Sonja Lang went through a period of depression and decided to create a new language to sort her thoughts?

Scott: I’ve never heard of language therapy before. Except maybe in 1984, and that didn’t go so well.

jan Alise: Toki Pona is much closer to cognitive therapy than it is to Newspeak. You know how cognitive therapy teaches to recognize one’s thoughts as that – just thoughts? In Toki Pona, there is no single word for thought, so it pushes speakers to think about what the “thought” really means.

Scott: And that helps?

jan Alise: For example, you could use “toki insa”, inside talk, to describe it. Maybe this makes you more receptive to the idea that thoughts are just talk, and could be true or false or in-between.

Scott: I see… but if “toki insa” is the compound expression for thought, you have merely substituted one expression for another. It will become automatic, and people will forget the original meaning. Just like nobody realizes that “happen” and “happy” are related 3.

jan Alise: You are right. This is why the Toki Pona community tries to avoid fixed compound expressions – what we call lexicalization. How about “pilin sona”, the feeling of knowledge, for thought? That might be more fitting for the process of recalling a memory. Or “pali lawa”, work of the head, for concentrated thoughts. “musi insa” is inside play. Wouldn’t that describe creative thoughts? There are so many possibilities.

Scott: In therapy, we usually try to help the patient, not confuse them further with many possibilities.

jan Alise: Sorry, I did not want the examples to feel overwhelming. I meant that using Toki Pona encourages you to think of these options, and in doing so, define more precisely what your thoughts really are. When someone is ruminating or has automatic thoughts, these are often detached from reality. Expressing them with the limited Toki Pona vocabulary connects the thoughts with the universal experiences that the words are about.

Scott: That sounds like the linguistic relativity theories that started with Sapir and Whorf. Aren’t these heavily debated?

jan Alise: They sure are. I am not arguing for any strong form of linguistic relativity, which claims that language determines your thoughts. But subjectively, I’ve experienced how thoughts become clearer and closer to my basic needs, when I express them with Toki Pona.

Scott: This is cool. Yet, being a psychiatrist, I have learned that people have complex, interlocked problems. One does not simply reduce a human’s psyche to language alone. For example, there is much more to gender dysphoria than using the right pronouns.

jan Alise: And yet, an inclusive language with just a single pronoun might be a breath of fresh air.

Scott: And so all the genderqueer people flock to Toki Pona?

jan Alise: I admit they are strongly represented in the community. The community is very diverse and international though. People meet online, make music, write books, have meetups.

Scott: You are telling me people actually speak Toki Pona?

jan Alise: It’s one of the most successful constructed languages. More popular than Klingon by far. Second to Esperanto. There are some tens of thousands of speakers. Not many, but if you think of speakers per word…

Scott: Relatively speaking, I am less skeptical than before. But in absolute terms my skepticism is still high. Why would people do this?

jan Alise: For most, it’s a fun little project. But the language enables genuinely new things. For example, learning to read Chinese is out of reach for most people, but if there are just 120 words, you can pick up a logographic writing system effortlessly as part of learning the language.

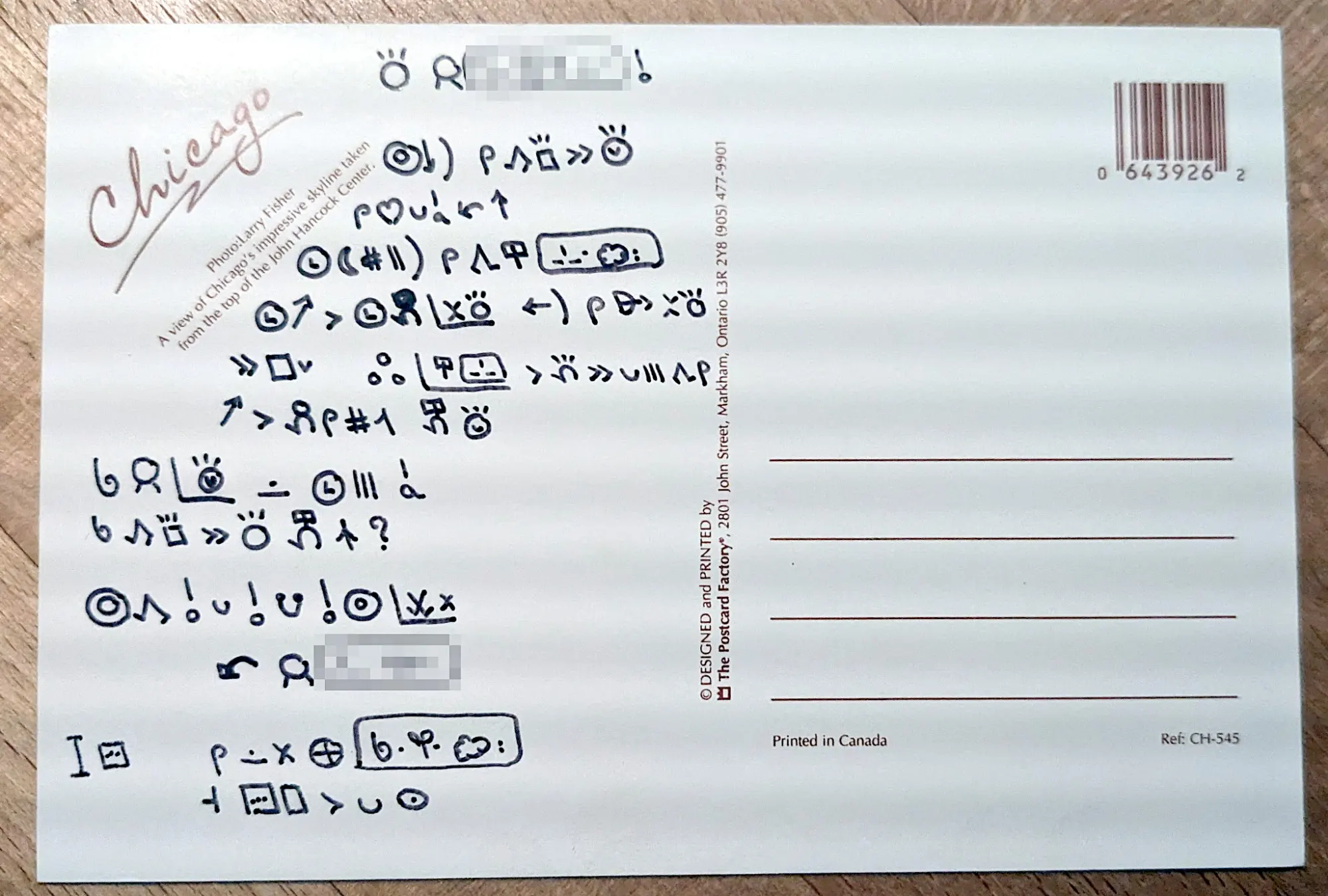

A postcard written in Sitelen Pona, a logographic system where each symbol is one word. The first line reads “sike ni la, mi kama sona e toki pona” – this year, I came to know Toki Pona.

Scott: There is a logographic writing system?

jan Alise: Yes. It is called Sitelen Pona, good writing. And there is an active sign language community, too. It’s all made possible by the small vocabulary. 120 words seems like a sweet spot, just like early computers used 120-ish ASCII codes to do everything they did.

Scott: That might be coincidental. Although, maybe we should explore the use of Toki Pona for AI? As a reasoning language, it would produce a smaller vocabulary and probably better embeddings… but NO! Toki Pona could become a kind of Neuralese. We must avoid this at all costs!

jan Alise: You seem to know a lot more about AI than I do. As someone who is not an expert, I just find it interesting that AIs recently started to understand and produce Toki Pona 4. But making AI good might be out of reach even for Toki Pona.

Scott: There could be new insights about learning efficiency. We should explore Toki Pona tasks for LLM benchmarking. I’ll set aside an ACX grant for this. Alice, your language might yet be of use. Imagine the interpretability research made possible when we search activation patterns for each of the 120 words! Imagine humanity’s last unscraped secrets, kept in logographic writing on someone’s paper notebook. This could be our last chance … or … actually … Alice, have you ever heard of someone enumerating Toki Pona word combinations to find names of God?

jan Alise: What a silly project 5! You make no sense, Scott. Toki Pona is less serious than that. Take kijetesantakalu, for example.

Scott: ki-what? If that’s a name of God, it must have been hard to find.

jan Alise: It’s a word for racoons and related animals. jan Sonja introduced it in 2009 on April Fools’ Day. The word was meant to be temporary, but people loved it and kept using it. It has become a bit of a mascot.

Scott: You’re telling me this language of supposed ultimate simplicity has… whimsical, arbitrary elements?

jan Alise: It does. Which might well mean that it is completely unlike drug reviews, after all.

Scott: I’m not so sure ;-) Let’s meet again for another post to discuss this. In the meantime, stay pona!

Footnotes

-

Njal’s Saga has 1200 unique words, give or take, depending on the amount of normalization: from “a” (used 116 times) to “your” (used 25 times). ↩

-

The words that jan Alice used, in order of appearance in the text:

toki: to talk, to explain, communication, language

jan: person, human being. jan Alise is Alice, lit: the Alice-y person

pona: good, simple

sina: you, your

ken: can, to be able to, to be possible

ala: not (negates the word before it)

e: object marker (separates the verb and the object in a sentence)

ijo: thing

la: context marker (the part before “la” is context for what follows)

sona: to know, to understandThe grammar outline introduces three new words:

li: verb marker (separates the subject and the verb in a sentence)

mi: I, my

ni: this (points to something else)Alice’s discussion with Scott continues:

insa: inside, inner

tan: because of, origin

pana: to give, to put

tawa: towards, to

mute: many, any number more than two

pi: a particle that groups modifiers. “jan toki pona” means (jan toki) pona – the good speaker. “jan pi toki pona” means jan (toki pona) – the person of a good language.

mani: money, livestock

luka: hand, arm; the number five

wile: want, need

tu: to separate; the number two

nanpa: number. Starts an enumeration: the first, the second, …

wan: a part, a whole; the number one

o: vocative marker (introduces a wish or order)

kama: to come, to arise, to appear

ike: bad, complex

a: ah, exclamation (emphasizes the word before it)

supa: a surface, a table

pakala: to break, to harmIn the rest of the text, she uses a few more:

pilin: to feel, feeling, the heart

pali: to work, to create

lawa: the head, to lead

musi: play, art ↩ -

Both “happen” and “happy” derive from medieval hap: chance, a person’s luck, fortune, or fate. ↩

-

For jan Alise’s n=1 experiment, she gave the same task to a number of LLMs, keeping the API calls as similar as possible. The prompt asked for a packing list for a two-day hike, in Markdown format with checkboxes:

Mi en jan pona li wile tawa nena. tenpo pimeja la, mi wile lape lon poka nena. tenpo suno kama la, mi wile tawa sewi nena.

mi sona e ni : suno li lon. telo sewi li lon ala. tenpo pimeja la, kon li ken lete lili.

mi o jo e ijo seme lon poki monsi? o sitelen e ijo ni kepeken nasin Markdown. ijo ale la, mi jo e ona la, mi luka e ijo. ni la, sitelen leko li kama sitelen pini.

Results based on her subjective rating:

GPT-4.1: Understanding 0/2, writing 1/3 = 1/5

o4 Mini High: Understanding 0/2, writing 1/3 = 1/5

Grok 3 Beta: Understanding 0/2, writing 1/3 = 1/5

DeepSeek V3: Understanding 1/2, writing 1/3 = 2/5

o3: Understanding 2/2, writing 2/3 = 4/5

Claude 3.7 Sonnet: Understanding 2/2, writing 3/3 = 5/5

Gemini 2.5 Pro: Understanding 2/2, writing 3/3 = 5/5 ↩ -

Toki Pona being a minimal language, it has fewer sounds than English. Toki Pona speakers replace complex sounds like “sc” or “x” with simpler ones. A name like Scott Alexander might become jan Sotalesante in Toki Pona 6.

Names of God would presumably include parts that are tokiponized, such as “sewi Jupite”. Due to the limited size of the Toki Pona alphabet, this reduces the search space, but probably not as much as Scott has hoped. Toki Pona uses the letters a, e, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, s, t, u, and w. The phonotactic rules require that each syllable starts with one of these, contains a vowel, and may optionally end in -n. The syllables “wu”, “wo”, “ji”, and “ti” are excluded for being hard to distinguish. So any tokiponized name of God would be formed of a combination of the 92 legal syllables. ↩

-

This might solve an important problem, if someone could just pitch Toki Pona to the New York Times. ↩